Victoria Memorial, Kolkata

Façade of the Victoria Memorial | |

| |

| Established | 1921 |

|---|---|

| Location | 1, Queens Way, Maidan, Kolkata, West Bengal 700071 |

| Type | Museum |

| Collection size | 50,000 |

| Visitors | 5 million annually |

| Founder | Lord Curzon |

| Curator | Samarendra Kumar |

| Architect | William Emerson, Vincent Esch |

| Owner | Government of India |

| Website | victoriamemorial-cal.org |

22°32′42″N 88°20′33″E / 22.5449°N 88.3425°E

The Victoria Memorial is a large marble monument in the Maidan in Central Kolkata, having its entrance on the Queen's Way. It was built between 1906 and 1921 by the British Raj. It is dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria, the Empress of India from 1876 to 1901.

It is the largest monument to a monarch anywhere in the world. It stands at 64 acres of gardens and is now a museum under the control of the Ministry of Culture, Government of India.[1] Possessing prominent features of the Indo-Saracenic architecture, it has evolved into one of the most popular attractions in the city.

History

[edit]

According to historian Durba Ghosh, Viceroy of India Lord Curzon's "plans for the historical museum that became the Victoria Memorial Hall predated Victoria's death in 1901. When he addressed a group at the Asiatic Society, he admitted that he had always planned to build such a historical museum. The queen's death had provided an appropriate occasion to monumentalize the empire."[2]

After Victoria's death on 22 January 1901, Curzon wrote to Lord George Hamilton, the Secretary of State for India on 24 January, noting the "importance of Victoria's matriarchy to promoting loyalist feeling."[3] He proposed the construction of a grand building with a museum and gardens.[4] Curzon said on 26 February 1901 in his address to the Asiatic Society,

"Let us, therefore, have a building, stately, spacious, monumental and grand, to which every newcomer in Calcutta will turn, to which all the resident population, European and Native, will flock, where all classes will learn the lessons of history and see revived before their eyes the marvels of the past; and where father shall say to son and mother and daughter — ‘This Statue and this great Hall were erected in memory of the greatest and best Sovereign whom India has ever known. She lived far away over the seas, but her heart was with her subjects in India, both of her own race, and of all others. She loved them both the same. In her time, and before it, great men lived, and great deeds were done. Here are their memorials. This is her monument.’[5]

The government officials, princes, politicians, and people of India responded generously to Lord Curzon's appeal for funds, and the total cost of construction of the monument, amounting to one crore, five lakhs of Rupees, was entirely derived from their voluntary subscriptions.[6][5]

The site chosen was near the present-day Raj Bhawan, known at the time as Government House. The construction of the Victoria Memorial was delayed by Curzon's departure from India in 1905, with a subsequent loss of local enthusiasm for the project. There was also some uncertainty about the strength of the foundations, and tests on them were carried out.[7] On 4 January 1906, George, the Prince of Wales laid the foundation stone.[8]

The work of construction was entrusted to Messrs. Martin & Co. of Calcutta, and work on the superstructure began in 1910.[8] In 1911, before construction was finished, George V, the Emperor of India, announced the transfer of the capital of India from Calcutta to New Delhi.[9] Thus, the Victoria Memorial would come to stand in what would be a major provincial capital, rather than the national capital. The Victoria Memorial was completed and formally opened to the public in December 1921 by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII.[7][8][10]

After 1947, some additions were made to the Memorial.

A smaller Victoria memorial was also constructed in the Hardoi district in North-Western Provinces (in modern Uttar Pradesh), which has since been converted into a city club for recreation. Mahatma Gandhi addressed meetings in Hardoi in the 1930s.

Design and architecture

[edit]

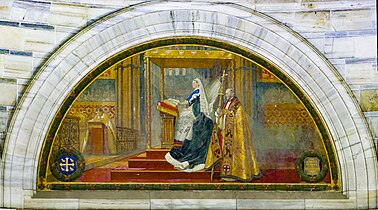

The architect of the Victoria Memorial was William Emerson (1843–1924).[11][12] The design is in the Indo-Saracenic style, mixing British and Mughal elements with Venetian, Egyptian, and Deccani architectural influences.[13] The building is 338 by 228 feet (103 by 69 m) and rises to a height of 184 feet (56 m). It is constructed of white Makrana marble.[14] Curzon deliberately intended the central chamber to be sixty-four feet in diameter in order to be slightly larger than the Taj Mahal. In design it echoes the Taj Mahal with its dome, four subsidiaries, octagonal-domed chattris, high portals, terrace, and domed corner towers. He also suggested that on the walls might be inscribed in golden letters Victoria’s proclamation of 1858. Around the interior walls of the rotunda of the memorial are a series of twelve canvas lunettes by Frank Salisbury celebrating key moments in Victoria’s life, such as her first Privy Council — moments already mythologized in countless other biographies, prints, and paintings.[3]

The gardens of the Victoria Memorial were designed by Lord Redesdale and David Prain. Emerson's assistant, Vincent Jerome Esch, designed the bridge of the north aspect and the garden gates. In 1902, Emerson engaged Esch to sketch his original design for the Victoria Memorial.

On top of the central dome of the Memorial is the 16 ft (4.9 m) figure of the Angel of Victory by Esch, which was cast by H.H. Martyn & Co. of Cheltenham.[15] Surrounding the dome are allegorical sculptures including Art, Architecture, Justice, and Charity and above the North Porch are Motherhood, Prudence and Learning.

The Victoria Memorial would end up with two statues of Victoria rather than one. George Frampton had been commissioned to produce a statue in Calcutta to commemorate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee in 1897. "Cast in bronze and depicts an enthroned and aged Victoria, looking down on her world while wearing the robes of the Star of India and holding the orb and sceptre." It arrived in Calcutta in 1902 and was unveiled on the maidan by Lord Curzon. In January 1914, Curzon commissioned Thomas Brock, who had also created the Victoria Memorial in London to produce a statue of Victoria in her coronation robes to serve as the 'keynote' of the central hall.[3]

The bronze gate at the entrance to the memorial, bearing the royal coat of arms, was also cast by Martyns.

Museum

[edit]The Victoria Memorial has 25 galleries.[16] These include the royal gallery, the national leader's gallery, the portrait gallery, central hall, the sculpture gallery, the arms and armory gallery, and the newer, Kolkata gallery. The Victoria Memorial has the largest single collection of the works of Thomas Daniell (1749–1840) and his nephew, William Daniell (1769–1837).[17] It also has a collection of rare and antiquarian books such as the illustrated works of William Shakespeare, the Arabian Nights and the Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam as well as books about kathak dance and thumri music by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. However, the galleries and their exhibitions, the programmatic elements of the memorial do not compete with the purely architectural spaces or voids.[18][19]

Victoria Gallery

[edit]The Victoria Gallery displays several portraits of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and paintings illustrating their lives, by Winterhalter, Frank Salisbury, and W. P. Frith.[20] These are copies of works of art in England. They include Victoria receiving the sacrament at her coronation in Westminster Abbey in June 1838; Victoria's wedding to Prince Albert in the Chapel Royal at St James's Palace in 1840; the christening of the Prince of Wales in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, 1842; the wedding of the Prince of Wales to Alexandra of Denmark in 1863; and paintings of Victoria at the service for her Golden Jubilee at Westminster Abbey in 1887 and her Diamond Jubilee service at St Paul's Cathedral in June 1897. Queen Victoria's childhood rosewood pianoforte and her correspondence desk from Windsor Castle stand in the center of the room, having been presented to the Victoria Memorial by her son Edward VII. On the south wall hangs the oil painting by Vasily Vereshchagin of the state entry of the Prince of Wales into Jaipur in 1876.[20][21][22]

Kolkata gallery

[edit]In the mid-1970s, the matter of a new gallery devoted to the visual history of Kolkata was promoted by Saiyid Nurul Hasan, the minister for education. In 1986, Hasan became the governor of West Bengal and chairman of the Victoria Memorial board of trustees. In November 1988, Hasan hosted an international seminar on the Historical perspectives for the Kolkata tercentenary. The Kolkata gallery concept was agreed and a design was developed leading to the opening of the gallery in 1992.[5] The Kolkata gallery houses a visual display of the history and development of Kolkata when the capital of India was transferred to New Delhi. The gallery also has a life-size diorama of Chitpur road in the late 1800s.[23]

Gardens

[edit]

The gardens at the Victoria memorial cover 64 acres (260,000 m2) and are maintained by a team of 21 gardeners. They were designed by Redesdale and David Prain. On Esch's bridge, between narrative panels by Goscombe John, there is a bronze statue of Victoria, by George Frampton. Empress Victoria is seated on her throne. In the paved quadrangles and elsewhere around the building, other statues commemorate Hastings, Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, Robert Clive, Arthur Wellesley, and James Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie. To the south of the Victoria, Memorial building is the Edward VII memorial arch. The arch has a bronze equestrian statue of Edward VII by Bertram Mackennal and a marble statue of Curzon by F. W. Pomeroy. The garden also contains statues of Lord William Bentinck, governor-general of India (1833–1835), George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon, governor-general of India (1880–84), and Rajendra Nath Mookerjee, a pioneer industrialist of Bengal.[5] Following an order of the West Bengal High Court in 2004, an entry fee was imposed for the gardens, a decision welcomed by the general public except for few voices of dissent.[24]

Gallery

[edit]-

Victoria Memorial with St. Paul's Cathedral, Kolkata, in the foreground.

-

Victoria Memorial illuminated at night.

-

Victoria Memorial Illuminated at night

-

Summer sunset

-

Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata

-

Lakes of victoria

-

The moon and Angel of Victory at Victoria Memorial

-

South side

-

King Edward VII Arch in the Victoria Memorial Gardens.

-

George Frampton's statue of Queen Victoria outside the Victoria Memorial Hall

-

Lion statue at Victoria Memorial

-

Victoria Memorial and The 42.

-

A sculpture of a Mother holding a child in one hand and a sword in the other hand

-

Statue of Motherhood

-

Gallery under the dome with scenes from the life of Queen Victoria: 1. The Apotheosis of Queen Victoria’s reign

-

2. 1887 Golden Jubilee Service at Westminster Abbey

-

3. 1897 Diamond Jubilee Service at St Paul's Cathedral

-

4. 1901 lying in state of Queen Victoria.

References

[edit]- ^ Victoria Memorial Archived 2 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine. www.iloveindia.com.

- ^ Ghosh, Durba (March 2023). "Stabilizing History through Statues, Monuments, and Memorials in Curzon's India". The Historical Journal. 66 (2): 348–369. doi:10.1017/S0018246X22000322. ISSN 0018-246X.

- ^ a b c Plunkett, John (9 February 2022). "A Tale of Two Statues: Memorializing Queen Victoria in London and Calcutta". 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century. 2022 (33). doi:10.16995/ntn.6408. hdl:10871/129016. ISSN 1755-1560.

- ^ Herbert E. W. "Flora's Empire: British Gardens in India." (Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), p. 224. ISBN 0-8122-0505-7

- ^ a b c d Dutta K. "Kolkata: a cultural and literary history." S – 131. ISBN 1-902669-59-2

- ^ "History of the Victoria Memorial Hall". Official Website of the Victoria Memorial Hall. Archived from the original on 13 June 2003.

- ^ a b Sharma A. "Famous monuments of India." Pinnacle Technology, 2011. ISBN 1-61820-545-5

- ^ a b c "Monuments - Victoria Memorial - Culture and Heritage - Know India: National Portal of India". Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Gordon D. (ed.) "Planning twentieth-century capital cities." (Planning, History and Environment Series. Routledge, 2006) p. 182 ISBN 0-203-48156-9

- ^ Plunkett, John (9 February 2022). "A Tale of Two Statues: Memorializing Queen Victoria in London and Calcutta". 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century. 2022 (33). doi:10.16995/ntn.6408. hdl:10871/129016. ISSN 1755-1560.

- ^ "Victoria Memorial." Archived 10 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine www.kolkatainformation.com.

- ^ Kumar R. "Essays on Indian art and architecture." Discovery Publishing House, 2003. p16. ISBN 8171417159, 9788171417155. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Knight L. "Britain in India, 1858 – 1947." Anthem Press, 2012. p85. ISBN 0-85728-517-3, 9780857285171. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Hermann M. "Architecture in India." GRIN Verlag, 2011. ISBN 3-640-92977-2, 9783640929771. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Whitaker, John, "The Best: a history of H.H. Martyn & Co", 1985, Page 136

- ^ Chander P. "India past and present." APH Publishing, 2003. p148 ISBN 8176484555, 9788176484558. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Freitag W. M. "Artbooks: a basic bibliography of monographs on artists." 2503. Victoria Memorial (Calcutta). A descriptive catalog of Daniells work in the Victoria Memorial (Museum). 1976. Routledge, 2nd edition, 2013. ISBN 1-134-83041-6, 9781134830411. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Dutta A. "The Bureaucracy of beauty: design in the age of its global reproducibility." Routledge, 2013 p294. ISBN 1-135-86402-0, 9781135864026. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ Moorhouse G. "Calcutta." Faber & Faber, 2012. ISBN 0-571-28113-3, 9780571281138. Accessed at Google Books, 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b "The Royal gallery." www.victoriamemorial-cal.org. Archived 24 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Dutta A. "Gallery reopens at Victoria Memorial after a decade." The Hindu, 12 September 2012. Accessed 14 December 2013.

- ^ Victoria Memorial Hall. Archived 6 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine www.culturalindia.net. Accessed 14 December 2013.

- ^ "Calcutta Gallery." www.victoriamemorial-cal.org. Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 1 January 2017.

- ^ "Victoria Fee for Good Cause". Times of India. 21 December 2004. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1921 establishments in India

- Art museums and galleries in Kolkata

- Buildings and structures completed in 1921

- City museums

- Gardens in India

- 20th century in Kolkata

- Marble buildings

- Monuments and memorials to Queen Victoria

- Monuments and memorials in Kolkata

- Museums established in 1921

- Museums in Kolkata

- Tourist attractions in Kolkata

- Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture

- National museums of India

- 20th-century architecture in India